Freedom of Association and Assembly / Protests, Political Expression

Microtech Contracting Corp. v. Mason Tenders District Council of Greater New York

United States

Closed Expands Expression

Global Freedom of Expression is an academic initiative and therefore, we encourage you to share and republish excerpts of our content so long as they are not used for commercial purposes and you respect the following policy:

Attribution, copyright, and license information for media used by Global Freedom of Expression is available on our Credits page.

Malta’s First Hall of the Civil Court in its Constitutional Jurisdiction held that the systematic destruction by government workers of a memorial in honor of slain journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, constituted a violation of protesters’ right to freedom of expression. Ever since the day after Caruana Galizia was murdered, activists, journalists and citizens have participated in a sustained campaign calling for justice which included maintaining a memorial to her in front of a national monument and organizing monthly protests. A government minister had ordered the routine “cleaning” or removal of all the banners, flowers, signs and related objects in an alleged effort to protect the national monument. The Court held that the Minister’s order was arbitrary and had the specific purpose of hindering ongoing protests. The Court noted that the location of the memorial in front of the Court of Justice, where follow-up investigations into the murder were conducted, was directly relevant for the purpose of the protests. Further, the material was easily removable and did not damage the monument. Citing substantial case law from the European Court of Human Rights, the Court concluded that the order was not provided by law, did not pursue a legitimate aim, and was not necessary in a democratic society. Thus the Court found a violation of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (freedom of expression) and Article 41 of the Constitution of Malta (protection of freedom of expression).

This case analysis was made possible by a generous contribution from The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation.

The plaintiff in the case was Emanuel Delia, a civil society activist and blogger in Malta.

After investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated on 16th October 16th by a car bomb, her sons, followed later by journalists, activists and Maltese citizens, created a memorial in her honor at the base of the Great Siege monument on Republic Street in Valletta (Malta), directly in front of the Court of Justice of Malta.

It is believed that her murder was in retaliation for her reporting and activism to uncover corruption at the highest levels of the Government of Malta. The main suspects behind her murder were persons whom she had investigated as part of her reporting. Despite an international team of investigators, progress was slow in determining who was responsible for ordering and implementing the attack. Therefore, protests against the climate of impunity surrounding the investigation into her killing are held in front of the Monument on 16th of each month.

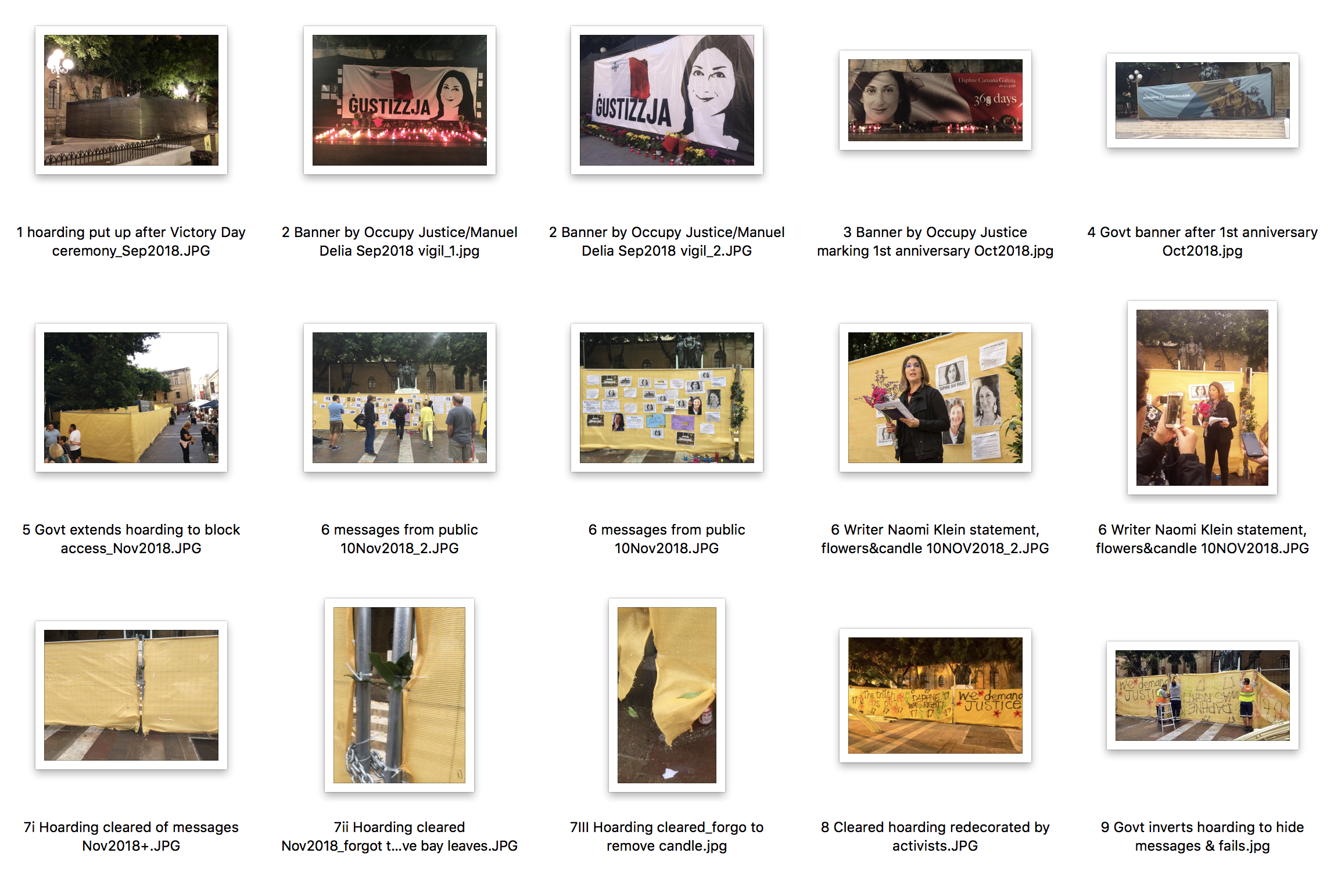

In the morning of Saturday September 25th, 2018 Emanuel Delia (hereinafter “the plaintiff”) and other Maltese activists placed a banner on the hoarding, a temporary protective fence, around the Great Siege monument. The banner represented the Maltese flag with the word “JUSTICE” and a picture of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. They also placed flowers, candles and other related objects in front of the banner.

Later on the same day, the banner, flowers, candles and other objects were removed by Government workers, namely by the Cleansing and Maintenance Division workers within the Ministry of Justice, Culture and Local Government (hereinafter “the Minister of Justice”). All objects, including the banner, were returned to the plaintiff by the police. Immediately after he left the police station, the plaintiff re-hung the banner on the hoarding by the Great Siege monument and placed the flowers, candles and other objects on the ground in front of the monument. The plaintiff did so in order to prepare for a commemoration scheduled for the following day, 16th September, eleven months after the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

In light of this, the plaintiff had to watch over the memorial during the night of 15th September and on 16th to make sure the banner, candles and other objects were not removed. At 4 am in the morning the government workers came to remove the said protest material but when they saw the plaintiff at the location, they decided to leave. They came back and removed all material on 18th September.

The plaintiff again filed a report with the Valletta Police Station. There, he was informed that the Minister of Justice Owen Bonnici had personally given instructions to the Cleansing and Maintenance Division for the removal. All material was returned to the plaintiff who immediately went back to the monument with other activists to again place the flowers, candles, objects in front of the banner as before.

The same scenario ensued on 19th September, when in the early morning hours the government workers removed everything again but this time the material was not returned to the plaintiff as on previous occasions.

The plaintiff then filed a complaint before the Constitutional Court of Malta for violation of his rights to freedom of expression as protected under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Convention”) and Article 41 of the Constitution of Malta (hereinafter “the Constitution”). He argued that the consistent removal by State authorities of the memorial objects violated his right to freedom of expression as they were intended to protest against the climate of impunity around Caruana Galizia’s murder in Malta. This interference was not legitimate as it was not prescribed by law, did not pursue a legitimate aim and was not necessary in a democratic society.

More specifically, the plaintiff claimed that the order from the Minister of Justice was arbitrary and did not comply with any existing law in Malta. The removal of the protest material did not pursue any legitimate aim listed in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Further, the interference could not be considered necessary in a democratic society as there was no “pressing social need” or evidence that the memorial infringed in any way on everyday life and activities. The plaintiff further argued that the interference also amounted to a form of censorship. He additionally claimed violations of Article 6 (access to court) and Article 13 (right to an effective remedy) ECHR.

The Minister of Justice, as respondent in this case, referred to the non-absolute nature of the right to freedom of expression that can therefore be subject to restrictions. In this case, the interference was prescribed by law, namely the Cultural Heritage Act which protected national monuments, qualifying as cultural heritage, from being damaged. Under the Abandonment, Dumping, Disposal of Waste in Streets and Public Places or Areas Regulations, placing objects in a public place which resulted in a “disorderly appearance of such place or which may be a nuisance to the public” could be prohibited. Following this regulation, State authorities had an obligation to clean up any objects left at the location within twenty-four hours. The respondent authorities argued that the plaintiff’s right to freedom of expression could not be exercised in such a way to cause damage to or deface the Monument.

The First Hall of the Civil Court in its Constitutional Jurisdiction (hereinafter “Court) began by recalling that the right to freedom of expression is an essential element of a democratic and pluralistic society. Therefore, the State not only has a negative obligation not to interfere with that right which enables social progress and individual development, it also has also a positive obligation to preserve and protect the expression of ideas, even those that offend, provoke, shock or disturb. It noted that the right is not absolute and that Article 10(2) of the European Convention of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Convention”) provides an exhaustive list of circumstances where State authorities could legitimately interfere with the right to freedom of expression. However, the validity of any restriction is subject to the three-part test, which requires it is prescribed by law, pursues a legitimate aim, or is necessary in a democratic society.

Article 41 – Maltese Convention

The court firstly set out the right not to be “hindered in the enjoyment of freedom of expression” under Article 41 of the Maltese Constitution. In consideration of case-law of the Maltese Courts, the Court referred to the judgment “Mons Philip Calleja vs Inspector Dennis Balzan”, decided on the 25th June 1976, where the Court of Appeal stated that “One of the positive elements of freedom of expression is the choice of the medium of expression itself…” The Court also referred to the judgment in the case “Dr Eddie Fenech Adami noe vs The Commissioner of Police etc”, in which the Constitutional Court stated that, while it is “the duty of the authority responsible for maintaining public safety and public order”, this must never be achieved by “minimising the same rights and freedoms which would thus be illegally threatened.”

The Court then moved on to consider the Article 10 right under the Convention to freedom of expression.

Article 10 – European Convention on Human Rights

The Court set out the scope of the protection under Article 10, referencing “Law of the European Convention on Human Rights”, which stated that the right is to “be broadly interpreted so as to encompass not only the substance of information and ideas, but also a variety of forms”. Furthermore, the Court referenced the assessment of White & Ovey in “The European Convention on Human Rights”, in which they state that there is a “higher level of protection” to speech which contributes “towards social and political debate.”

The Court further referenced the case Handyside v. the United Kingdom which set out the value of the right to freedom of expression as “one of the basic conditions for the progress of democratic societies and for the development of each individual”. This right includes: the freedom for a person to hold an opinion, the right that a person receives information and ideas and the right to be given information and ideas. However, this right is not an absolute right. Any interference must be prescribed by law, pursue a legitimate aim and be necessary in a democratic society. In consideration of the necessity of the interference, the Court referenced the ruling in Janowski vs Poland, in which the ECHR remarked that necessary “implies the existence of a ‘pressing social need’”, and any restriction must be “proportionate to the legitimate aims pursued.”

Prescribed by law

In order to be prescribed by law, the law must be “public, accessible, certain and would have foreseeable consequences.” [p. 65] In the case of The Sunday Times v. the United Kingdom, the Court observed that “the citizen must be able to have an indication that is adequate in the circumstances of the legal rules applicable to a given case.” [p. 67] Applied in the case of Rotaru v. Romania, decided on 4 May 2000, the Court held that a law was not satisfactory as it was not “drafted and written with precision in order that the citizens could regulate themselves adequately.” [p. 67] This was expanded upon in the 2018 case of Magyar Jeti Zrt v. Hungary, in which the Court set out the “prescribed by law” requires not only the existence of an impugned measure in domestic law, but an assessment of the “quality of the law in question, which should be accessible to the person concerned and foreseeable as to its effects.”

The Court recalled the State’s argument that Art. 4(2) of Cap. 445 requires “Every citizen of Malta as well as every person present in Malta shall have the duty of protecting the cultural heritage…,” and that the Monument as an “immovable object” with historical value, constituted cultural heritage and that Art. 70(1)(a) of Cap. 445 “considers it a criminal offence those acts by any person who: ‘wilfully, or through negligence, unskillfulness or non-observance of regulations causes damage to or destroys any cultural property.’” [p. 92]

Applying these principles to the facts, the Court observed that the Monument itself was not the issue, rather the site. The “memorial,” as evidence provided before the Court showed, was not intended to be a permanent memorial, but was selected because it was a “prominent space” which would “catch the attention of the public,” and would serve as a good base for protests.

The memorial and the objects, served not only as a form of remembrance but also as a form of protest and warning message that “whoever has the responsibility to uphold the rule of law must ensure that all the persons who were directly or indirectly involved with the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia are brought to the courts, to take responsibility for their actions, and accept their justice.”

The Court also took note of the plaintiff’s argument that the objects were a symbolic way to keep the spirit of the protest alive and ongoing. Thus, even after the protests had concluded, the memorial was a reminder to all who passed by that justice had not been done. In light of that objective, the Court asked the plaintiff, “If the purpose is to prolong and keep the protest ongoing…Who would be attracted to the purpose of the protest if at the site of the protest there would only be extinguished candles and dead flowers?” Witnesses attested that, in fact, an activist was going twice a day to the site to replace candles and add fresh flowers. The Court thus rejected the State’s claim that the protest materials constituted “waste.”

Witness testimony confirmed that none of the activities by protestors caused any damage to the monument. The objects were easily removed from in front and off the wooden fencing which had been erected round the Monument and no flowers, candles or photos were found behind the protective fencing.

It followed that since the objects were removed from in front of the fencing, the laws regarding the protection of monuments and cultural heritage could not be applied. The law could only be applied, if the objects were removed directly from the Monument.

The Court then rejected the State authorities’ argument that the removal of the objects was part of a regularly scheduled cleaning routine. The Court found it “surreal” that the objects were removed more than 17 times shorty after they had been placed, as such swift cleaning was not carried out on any other public monuments nearby. The State failed to explain why the cleaning was so much more efficient at this particular monument.

The Court also highlighted that the cleaning policy prior to September 2018, when the facts of this case took place, stated that the Cleansing and Maintenance Division workers were not responsible for removing anything from in front of the monument. This policy was, however, changed by the decision made by Minister Owen Bonnici, and not because they constituted waste under the Abandonment, Dumping, Disposal of Waste in Streets and Public Places or Areas Regulations.

The Court further rejected the State’s argument that the cleaning order was issued due to damage to the monument. Over an 11 month period, prior to Minister Owen Bonnici’s order, there had been no complaints made, nor had any of the protest materials been removed. The Court expressed its concerns for the way this decision was made and implemented, noting that if the Monument had been damaged, the Superintendence for the Cultural Heritage would have been notified and there would have been a formal procedure for addressing the issue, rather than a direct phone call ordering the removal.

The Court stated that it was its “firm conviction, based on the entirety of the evidence acquired in this case, that the removal of the protest objects was carried out based on a specific plan and with the intention to hinder the plaintiff’s right, as well as that of others sharing the same opinion, to express those opinions freely, from that site, that is, a location situated opposite the main door of the Court building.”

It further considered that the purpose of the regular protests, held since the day after Daphne’s murder, was a “call and loud cry for justice to be done”. It further noted that her murder was related to the journalistic investigations which she was conducting into individuals very close to the Government. The protests demanded not only that the police investigations determine who ordered her assassination, but also that all the leads she was following at the time of her murder be pursued in an effort to uncover all the alleged crimes and the perpetrators behind them. The Court added that the location of the memorial was not a random choice, but intentionally staged in front of the Court of Justice where the police investigations into the murder were being conducted.

Based on the above, the Court concluded that the interference with the plaintiff’s right to freedom of expression was not prescribed by law.

Legitimate aim

The second test for the Court was whether or not the restriction in question pursued a legitimate purpose, listed under Article 10(2).

It was undisputed that the plaintiff’s purpose in maintaining the memorial and organizing the on-going protests was to keep pressure on the authorities to ensure justice was done and to hold the perpetrators to account. Considering that the memorial was maintained on a daily basis over a period of two years, it was clear based on evidence presented at the trial that the objects were not removed to protect the national Monument but to “hinder the continuation of the protests.” That aim did not fall within the scope of legitimate restrictions listed under Article 10(2) of the ECHR.

Necessary in a democratic society

The third and final test for the Court is whether or not the restriction was necessary in a democratic society. This requires that there must be proportionality between the purpose which has to be achieved and the means to achieve that purpose. The Court stated that “there is proportionality only if it is shown satisfactorily that the interference is based on a pressing social purpose. In the case of Kandzhov vs Bulgaria, the ECtHR observed that “the Government and of its members must be subject to close scrutiny by the press and public opinion.” Furthermore, in the case of Observer and Guardian s the United Kingdom, the ECtHR defined “necessary” in Article 10(2) to imply “the existence of pressing social need”.

Ultimately, the Court followed the principle set out in The Sunday Times vs the United Kingdom, that the Court should follow the most restrictive interpretation. In this case, “restrictive interpretation was interpreted to mean that “no other criteria than those mentioned in the exception clause itself may be at the basis of any restriction.”

The Court held that none of the reasons put forward by the respondent amounted to a pressing social need, sufficient to justify an interference with the plaintiff’s right to freedom of expression.

The Constitutional Court of Malta concluded that the plaintiff’s right to freedom of expression as protected under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Article 41 of the Constitution of Malta had been violated.

The Court ordered the State to pay EUR 1,000 to the plaintiff in non-pecuniary damages for removing the protest material from the memorial.

The Government did not appeal.

Decision Direction indicates whether the decision expands or contracts expression based on an analysis of the case.

The decision expands expression for several reasons. First, the Court declared that the objects used in front of the national monument in Valletta (Malta) , namely flowers, candles and other items were protest objects and served a protest purpose aimed at reminding the public and the authorities the call for justice.

Secondly, it expands the right to protest by declaring that placing a banner, flowers, candles and other objects in front of a national monument calling for justice for the murder of killed journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was a form of expression protected under Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights and Article 41 of the Constitution of Malta.

Thirdly, The Constitutional Court of Malta has set another important precedent for the right of protesters in Malta recognising that the removal of the protest objects had the intention to hinder not only the plaintiff’s right to freedom of expression but that of others with his same opinion. In July 2019, the same Court delivered another landmark ruling in relation to a banner placed by the family of Daphne Caruana Galizia questioning authorities about impunity for the killing of the journalist. In both cases, the Constitutional Court considered the decision of the Minister of Justice, in the first case, and of the Planning authority, in the second one, as arbitrary and in violation of the protester’s and family’s respectively right to freedom of expression.

Fourthly, the Constitutional Court expands the right to protest by recognising that although protests may have repercussions that annoy the State and the public opinion of those who do not share the protest purpose nor its form, this sentiment does not meet the necessity test and, therefore, is not sufficient to render the removal of the protest objects.

Global Perspective demonstrates how the court’s decision was influenced by standards from one or many regions.

Case significance refers to how influential the case is and how its significance changes over time.

Let us know if you notice errors or if the case analysis needs revision.