In this blog, CGFoE’s Editor Anastasiia Vorozhtsova reflects on the current state of the right to historical truth in Russia and the organization that continues to defend it. Memorial was awarded 2022’s Nobel Peace Prize, along with the Belarusian activist Ales Bialiatski and Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties, in recognition of their stand for human rights and democracy.

Filipp Terentievich Terentyev, 51, a carpenter at an orphanage, was executed on February 17, 1937, in Moscow. Varvara Ivanovna Brusilova, 38, a translator, nurse, and journalist, was executed on September 10, 1937. Zakhar Filippovich Pukhalo, 38, a welder at a plant, was executed on January 6, 1938, in Barnaul.

The list of the innocent—the old and the young; carpenters, journalists, welders; Poles, Tatars, Germans, Russians—has no end. Every year since 2007, it has been read aloud: in fractions, publicly, from 10 AM until 10 PM Moscow time. Organized by Memorial, Russia’s oldest and most prominent human rights organization, the Returning the Names action has now gone international. But it is no longer welcome at home.

Documenting the history of Soviet terror

“The action was my idea,” Elena Zhemkova, Managing Director of Zukunft [Future] Memorial (that is: Memorial in exile), told me recently at the opening of an exhibition in Hamburg. “I wanted to give people an opportunity to be brave.” Titled “The Other Russia,” the exhibition narrates the 35 years of Memorial’s work: a battle to preserve historical truth and resist autocracy—a battle, one can argue, Memorial has lost.

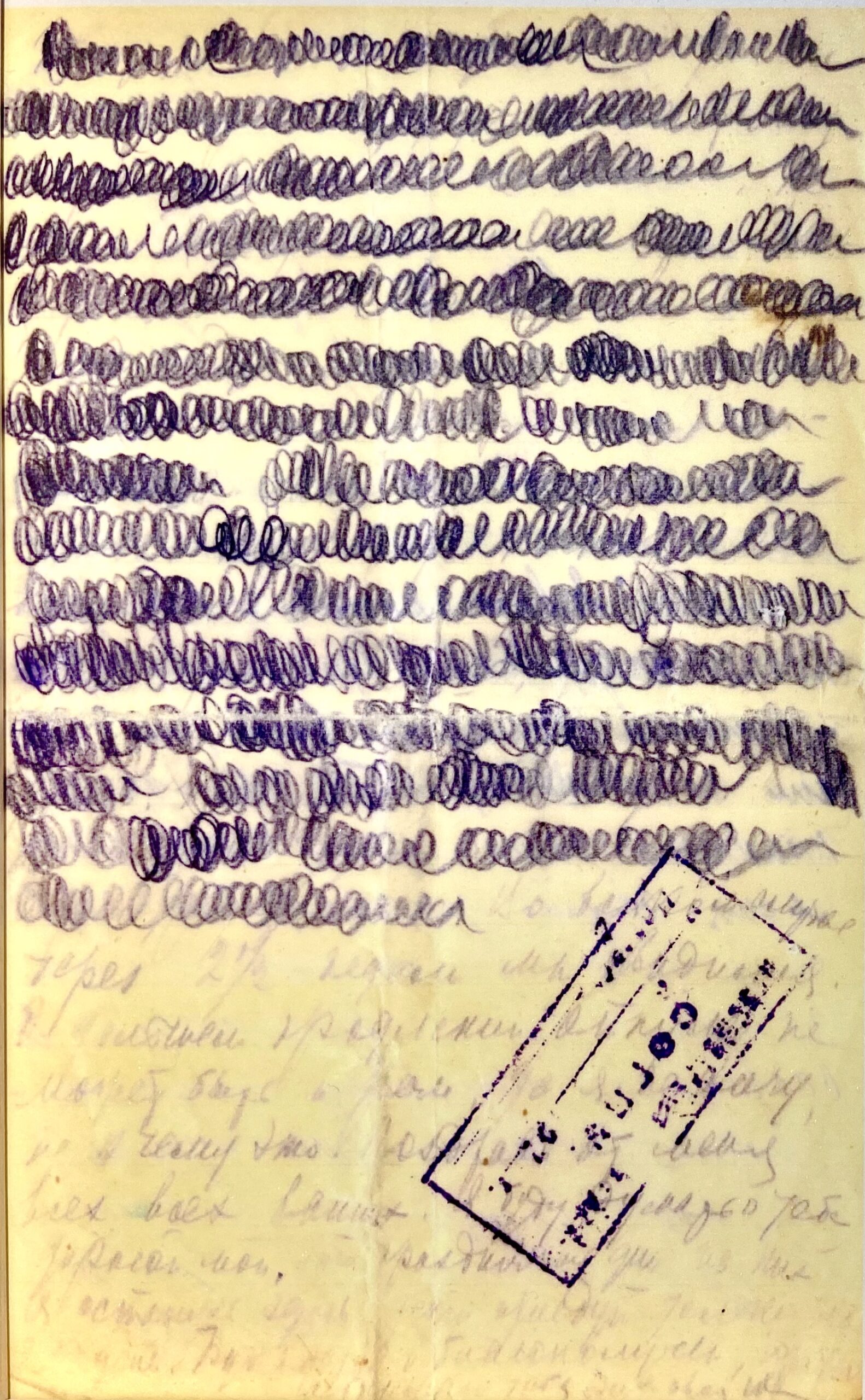

A prisoner’s letter, censored, Suzdal, 1924. Source: Memorial’s exhibition “The Other Russia” in Hamburg, Germany, January 2026.

Founded at the end of the 1980s, Memorial set out to document the history of Soviet terror, archiving the names of victims and perpetrators, prisoners’ fates, letters, testimonies. Thanks to this work, we know that the GULAG spread through the entire Soviet Union, and at least 18 million people were forced to go through its labor camps.

Memorial’s founders saw historical reckoning as a foundation for democracy. Yet Russia soon headed in the opposite direction. The organization began to monitor the country’s present-day repression, advocate for the freedom of political prisoners, and call out war crimes, opposing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine since 2014.

In 2016, the authorities designated Memorial a “foreign agent.” In 2021, the Supreme Court ordered Memorial’s liquidation: formally, for its failure to include the “foreign agent” banner on social media; but in court, the prosecutor argued that Memorial created a false image of the Soviet Union as “a terrorist state.”

Repression has no boundaries

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Memorial was declared illegal, and its offices were seized. Some staff members had to flee Russia. Oleg Orlov, Co-Chairman of Memorial’s Human Rights Defense Center, was charged with “discrediting the Russian army.” In a courtroom, as a statement, Orlov read Franz Kafka’s The Trial. Sentenced to 2.5 years in prison, he was later freed in a prisoner exchange.

“[The Russian authorities] today are scaring people into silence,” Elena Zhemkova told me at the exhibition. “And one of the features of this intimidation campaign is its lack of logic: repression has no boundaries. They can jail an old woman and a teenager.” (Russia’s youngest political prisoner, Arseny Turbin, was jailed at 15. Oleg Orlov, now 72, was one of the oldest.)

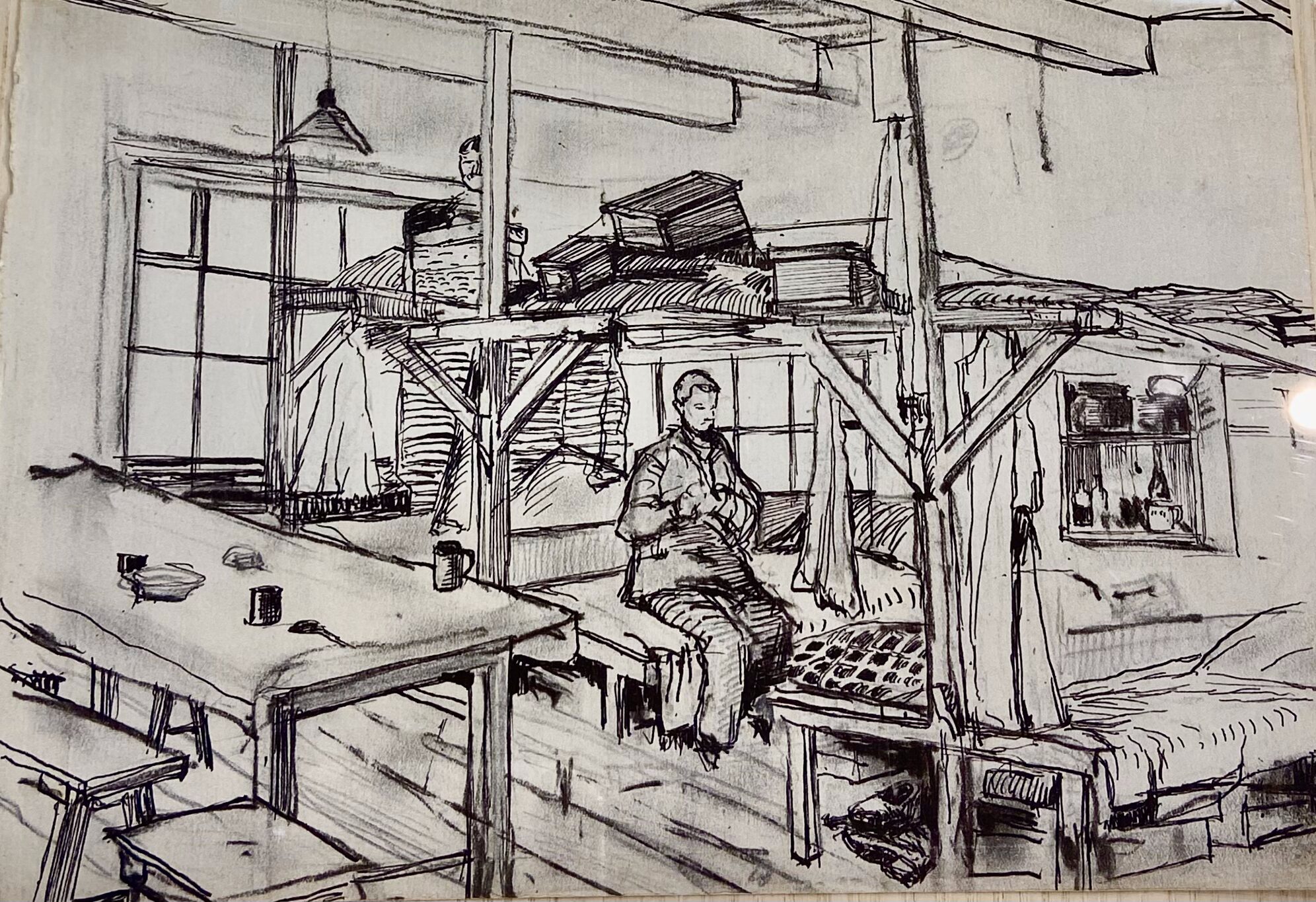

Drawing of a prisoner’s barracks by Ivan Sukhanov, Kemerovo, 1935/36. Drawing of the GULAG was possible only in secret. Many pictures were destroyed during searches. Sukhanov’s drawings are among the very few that survived. Source: Memorial’s exhibition “The Other Russia” in Hamburg, Germany, January 2026.

The government’s policy on the commemoration of Soviet victims used to say that “Russia cannot fully become a state governed by the rule of law […] without perpetuating the memory of the many millions of its citizens who became victims of political repression.” Even before removing the line by decree, the authorities had been repeatedly restricting Memorial’s access to government-held archives through laws and court decisions.

Waging a war against a neighboring state—and against dissidents at home—demands a near-total state control of history: a cherishing of the past’s glory, feeding national pride. Busts of Iosif Stalin reappear, eerily, across the country. The Last Address plaques in memory of victims of Soviet terror—similar to Europe’s Stolpersteine—go missing, leaving traces of hollow rectangular shapes.

Remembering the Soviet past means seeing contemporary Russia with clarity

In 2024, in a case with five applicants, one of them Memorial, the European Court of Human Rights held that Russia violated the right to freedom of expression by obstructing or denying access to historical archives on gross human rights violations. The archive, the Court recognized, is not passive: it can shape a public debate.

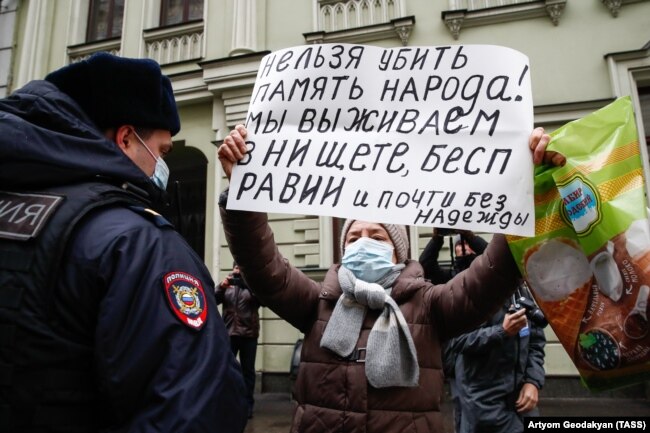

A woman protesting the prosecution of Memorial in November 2021. The sign reads, “You cannot kill the memory of the people! We are surviving in poverty, with no rights, and almost without hope.” Photo credit: Artyom Geodakyan (TASS)

These days, remembering the Soviet past means seeing contemporary Russia with clarity, seeing beyond the Kremlin-sanctioned lens of “only glory.” Soviet-era repression—its scale, its arbitrariness, its lack of logic—forced people to live in dread. Remembering the names and fates of its victims became, then and now, another kind of act: that of resistance.

When Returning the Names was first held in 2007, about two hundred people came. In 2019, the last year Moscow authorities allowed it, six to seven thousand stood in line in the capital alone. “You won’t make it [to the mic in time],” Elena Zhemkova told those waiting at the back. More people wished to join the action than the twelve hours made possible. Still, they stayed.

Today, the names are read outside Russia and by those inside the country who are willing to risk it. As archives continue to close, holding on to historical truth itself grows into a form of dissent. The voices of those speaking out the names—in a solemn rhythm, one at a time—echo across decades and borders, refusing to remain mute. They urge for justice then and, with great urgency, now.