As part of CGFoE’s interview series “Portraits of FoE Defenders,” we are featuring one of the world’s most prominent journalists and press freedom advocates: Maria Ressa. At a time of multiplying threats against democracy, the message Ressa shares is both a warning and a call to action.

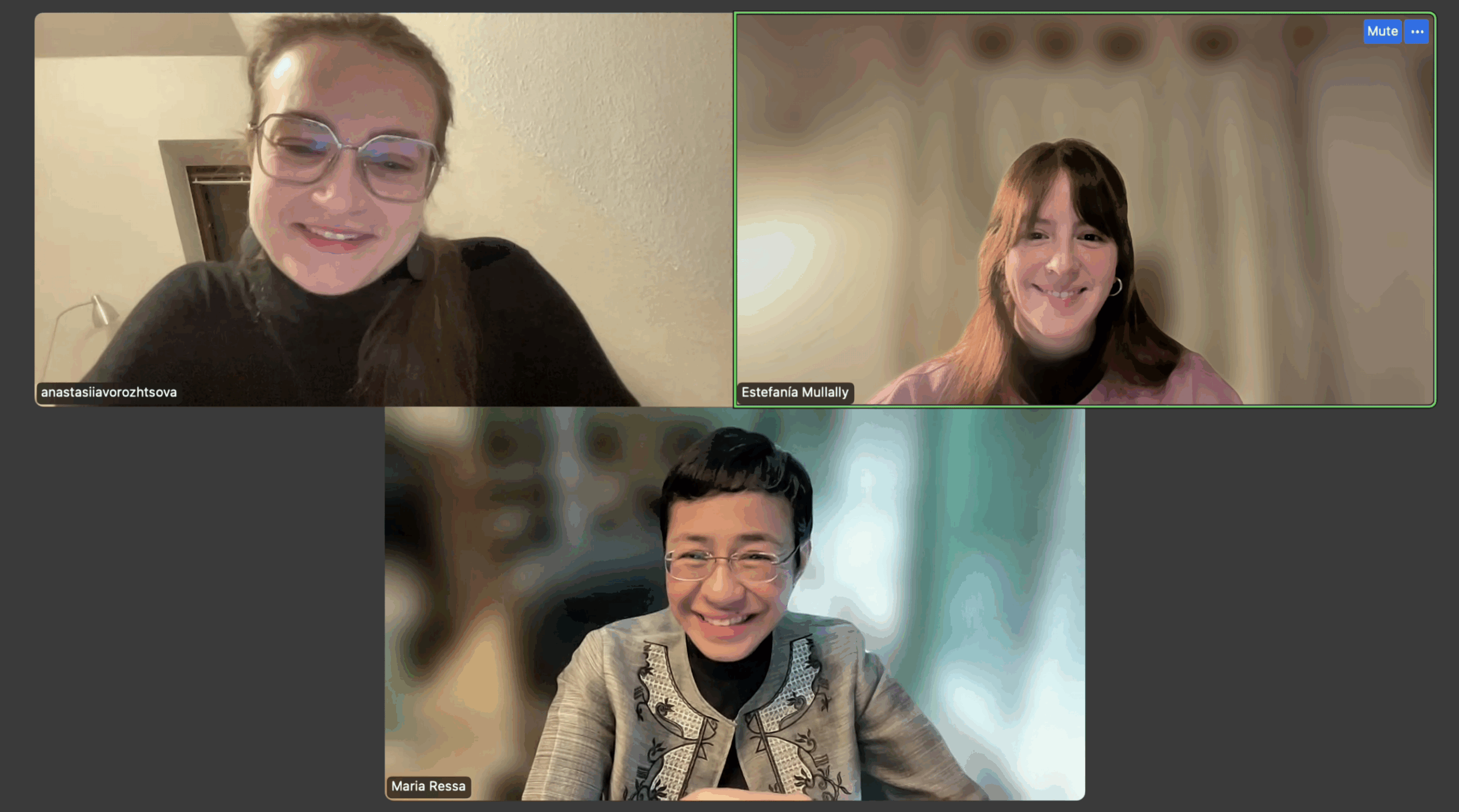

This August, CGFoE’s Program Coordinator Estefanía Mullally and Editor Anastasiia Vorozhtsova sat down with Maria Ressa, Nobel Peace Prize Winner, Co-Founder and CEO of Rappler, and Professor of Professional Practice at the School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, to discuss the state of global freedom of expression, the dangers of social media and generative AI, the challenges of being a woman journalist, and what it takes to confront authoritarianism today. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Maria Ressa is a Nobel Peace Prize-winning journalist, Co-Founder and CEO of Rappler, and Professor of Professional Practice at Columbia University. Photo: Ian DiSalvo

CGFoE: What does press freedom mean to you personally and professionally?

Maria Ressa: It was something I grew up with and took for granted. I spent twenty years with CNN and opened its Manila and Jakarta bureaus. I ran the news group of ABS-CBN, which was the largest broadcaster in the Philippines. But until you come under attack, you don’t know how essential groups like the Committee to Protect Journalists and coalitions of journalists are.

Over the last twenty years, as attacks on journalists have increased, the quality of democracy has decreased. They almost go hand in hand. In the 1980s, when I was covering South and Southeast Asia, I said that the quality of democracy depended on the quality of a country’s journalists. That is still true. But the difficulty today is the technology that we use.

Artificial intelligence is neither artificial nor intelligent

People talk a lot about artificial intelligence, which has been around for almost 70 years and is neither artificial nor intelligent. Social media and machine learning created models of us: Drop the word “model” and call it a “clone.” Neither social media nor generative AI is anchored in facts. Journalists are attacked on both. Our public information ecosystem is corrupted. Its basic tenet is personalization because the people who designed it were trying to sell us things. And if there are twenty people in a room with twenty different personalized realities, that actually, in the Old World, would be called an insane asylum. This is the world we live in today.

Tech companies found ways to insidiously manipulate. I always say they hacked our biology. Using the worst of our emotions – fear, anger, hate – they pushed us to change the way we see the world. In our data in the Philippines, in 2017, women were attacked ten times more than men. Leila de Lima, a sitting senator, was pummeled, probably a little bit worse than I was, and she spent nearly seven years in jail, unjustly. Even before social media, studies showed that people don’t vote because of their rational mind; 85% vote based on how they feel. Technology took it a step further. On social media platforms, lies spread six times faster – according to the 2018 MIT study, released before Elon Musk bought Twitter. We’re living in this toxic sludge.

When you change the way people feel and see the world, you change the way they act and vote. This power gives the ability to manipulate the cellular level of a democracy. From 2016 and all the way to 2024, every election saw this. I started pointing it out in 2021 at the Nobel lecture, but electoral integrity wasn’t addressed until November 2024, when Romania decided to void their elections because they had evidence of election manipulation. There’s a global dynamic happening. As of March this year, V-Dem in Sweden says that 72% of the world is now under authoritarian rule. We’re literally electing illiberal leaders democratically.

How has being a woman impacted your exercise of freedom of expression?

I was a war zone correspondent. In Southeast Asia, I covered the transition of almost all of our countries from authoritarian one-man rule to democracy. I started as a reporter in 1986, and the question then was: “How can you be a woman journalist in conflict areas?” I was like, “It actually works better when you’re a woman – you get a lot more done than those men who will want to punch each other out.” So I’d say: War zone coverage? Yes, absolutely. I ran a team.

The first time journalists were attacked for doing their jobs was in Indonesia in 1998, when white journalists were being attacked. Until then, people in the jungles – name any revolutionary group – needed and protected journalists. Revolutionary movements gave us not only safe passage, but also tried to get us to stay with them in the jungle. One example is the Falintil guerrillas in East Timor; another is the Communist rebellion in the Southern Philippines. Until 1998. A Dutch journalist and friend, Sander Thoenes, was killed in East Timor [in 1999] – to this day, there’s been no justice for his death. After that was Iraq. The Reuters journalist killed in Iraq was in East Timor and in Indonesia with me. Attacks on journalists reached their apex in Gaza.

People around the world are manipulated in the same way

In the Old World, being a woman journalist in conflict zones was great. I always felt that there should have been more of us. But, of course, there’ve been many. Marie Colvin, the woman journalist with an eye patch, was in East Timor with us and then was killed [in Syria, in 2012]. Women journalists have led.

In the age of social media and exponential lies, women journalists are the first to be attacked. And the line between information operations and information warfare is very thin. When you change the way people think – inject them with toxic sludge – it’s a tipping point in an epidemiological system. What’s a tipping point for the United States? How about the violence on Capitol Hill? All of that had been building underneath the surface, and then it tipped, and there was violence.

The only way I can spin positively what Big Tech has done is this: They showed us that, regardless of language, culture, or geography, people around the world are the same. We’re manipulated in the exact same way. And frankly, we should be learning a lot from that – a great starting point, which I wish the United Nations used. We are the same. And the two fracture lines in nearly every country where we’ve studied information operations are gender and race.

In what ways does gender shape the use of SLAPPs to silence women journalists?

It’s not just women. It’s women and men, but if you look at the pattern in the Philippines, the people who fight back are women. Duterte collapsed the institutions of democracy within six months of taking power. He targeted men and women. The people who fought back were women. His Vice President, Leni Robredo, who ran against him, who ran against Bongbong Marcos, was a soft-spoken woman. Leila de Lima, who was a senator and led the investigations into the drug war killings, whom his administration jailed, is a woman.

I always joke that the Nobel Peace Prize was nothing. I just kept doing my job, and it was because Duterte was so off the scale that, in a way, he gave us the Nobel. It’s women who have led the charge back. I look at the UK and journalists – Carole Cadwalladr has led that charge. There’s a UNESCO report from 2022 that became a book, The Chilling, [edited] by Julie Posetti [and Nabeelah Shabbir]. They used Carole and me as case studies. Women are the first to be attacked, and women are the first to push back. TV soundbite (laughing).

Did gender influence the way your court cases have been handled?

No, I mean, it’s like asking me whether being a woman journalist helped me or hindered me in war zones, right? Because at the time when I was doing conflict reporting, men were the ones making decisions. Frankly, Rappler is women-led, and we don’t make a distinction between genders. There shouldn’t be, because there are strengths and weaknesses of each one.

Duterte used sexism and misogyny to attack women, tapping into deep-seated biases. In the Philippines in 2013, we did a nationwide survey, and in the national capital region, we asked, “If you have a man and a woman as presidential candidates with identical qualifications, whom would you choose?” In a country that’s had two women presidents, 71% said they would choose the man. As Asia’s largest Roman Catholic nation, we grew up with these beliefs in our culture.

In the last, I would say, twenty years, we’ve been able to change these perceptions. But when you put people in power who have those biases, they perpetuate them. What Duterte did, as Trump is doing in the US, is permit the worst of our societies to be their worst selves. Instead of giving people agency, Duterte gave them someone to blame. You can see this in the rise of white supremacy globally.

As Western media face unprecedented obstacles – funding cuts, outright censorship, more and more lawsuits – what can they learn from more embattled parts of the world?

How to stand up, wake up, and fight back. It’s a simple thing, right?

In the 1990s, when I covered one of the Russian elections, I thought, “I hope our country doesn’t go here.” Now the entire world is following the trend of Russia. Anne Applebaum calls it “Autocracy, Inc.” We’ve always called it “Kleptocracy. Inc.” Because this is power and money. Look, the Philippines has had Marcos the first, the father, thrown out in the People Power revolt in 1986 for stealing ten billion US Dollars. Now this is global. The connections online are global, too. And yet the understanding of how they work is so muted.

Let’s take a look at 2023. After the release of ChatGPT, about 23 billion dollars was invested. That became an arms race. LLMs are imperfect and have an error rate as high as 79% and at best, maybe 16%. The chatbot we built in Rappler, which is anchored in the content we own, has an error rate below 2%. You can actually anchor it in facts, but they don’t have the incentive.

This year determines if journalism will survive

In 2023, with all that investment, startups began crawling news sites. Rappler doesn’t allow the scraping of our content. But they steal it. Cloudflare released a blog saying that Perplexity [an AI-powered answer machine] was now pretending to be human to bypass [website restrictions]. The scale of scraping reaches hundreds of thousands per minute. Will journalism survive? I would say this year will determine that. If no guardrails are put in place, small- and medium-scale news organizations will not be able to survive this time period. It’s an information Armageddon.

What can the West learn from more embattled parts of the world? I can summarize it into four things. There’s media capture – but before that, you already have social media information operations – followed by academic capture – we know this – followed by NGO capture – academic and NGO capture happen at about the same time – and then there is state capture.

Without facts, you can’t have truth; without truth, you can’t have trust

Journalism, depending on how diseased the public information ecosystem is, can fight back. But I say, over and over: Without facts, you can’t have truth; without truth, you can’t have trust. Without these three, you have no shared reality. You can’t begin to solve any problem, let alone existential ones like climate change. You cannot have democracy. I think I started saying this in 2016: Facts are the foundation of a democracy. You cannot have the rule of law without facts.

The time to act is becoming shorter and shorter. If democratic governments keep trying to fix the cascading failures instead of the root cause of the problem, which is facts, information… You can look at Brazil. I always joke that the Philippines and Brazil are similar: We went from hell to purgatory. You can actually recover. My cases went down. I had eleven criminal charges, eleven arrest warrants, and today I have one left of all those cases. But I fought for almost a decade.

What can you learn? God! Learn! Read. Look at other parts of the world. Act. In my book, How to Stand Up to a Dictator, I ask the one question that I was directing to Filipinos: “What are you willing to sacrifice for the truth?” That became very clear to me and to Rappler. And we’re being asked to sacrifice a lot more. Beyond that, if Americans, if those Westerners, if the Global North doesn’t act, you will lose your democracy, and it falls quickly.

What message would you share with the women confronting authoritarianism today?

Collaborate, collaborate, collaborate. That’s how we survived. News organizations need to stop competing with each other. We’re on the same side of facts. It’s radical collaboration.

I’ll go to the end of the Nobel lecture where I said, “We’re standing on the rubble of the world that was.” Our brains, the way we are, tend to not want to admit that. But the minute you do, you can begin to work together. At these times, when the world has turned upside down, the hope is to have the power to create what should have been. The Old World wasn’t fantastic – there were many things wrong with it. But if you do not act now, we’re going to fall off the cliff. And I mean the entire world – this isn’t just one country.