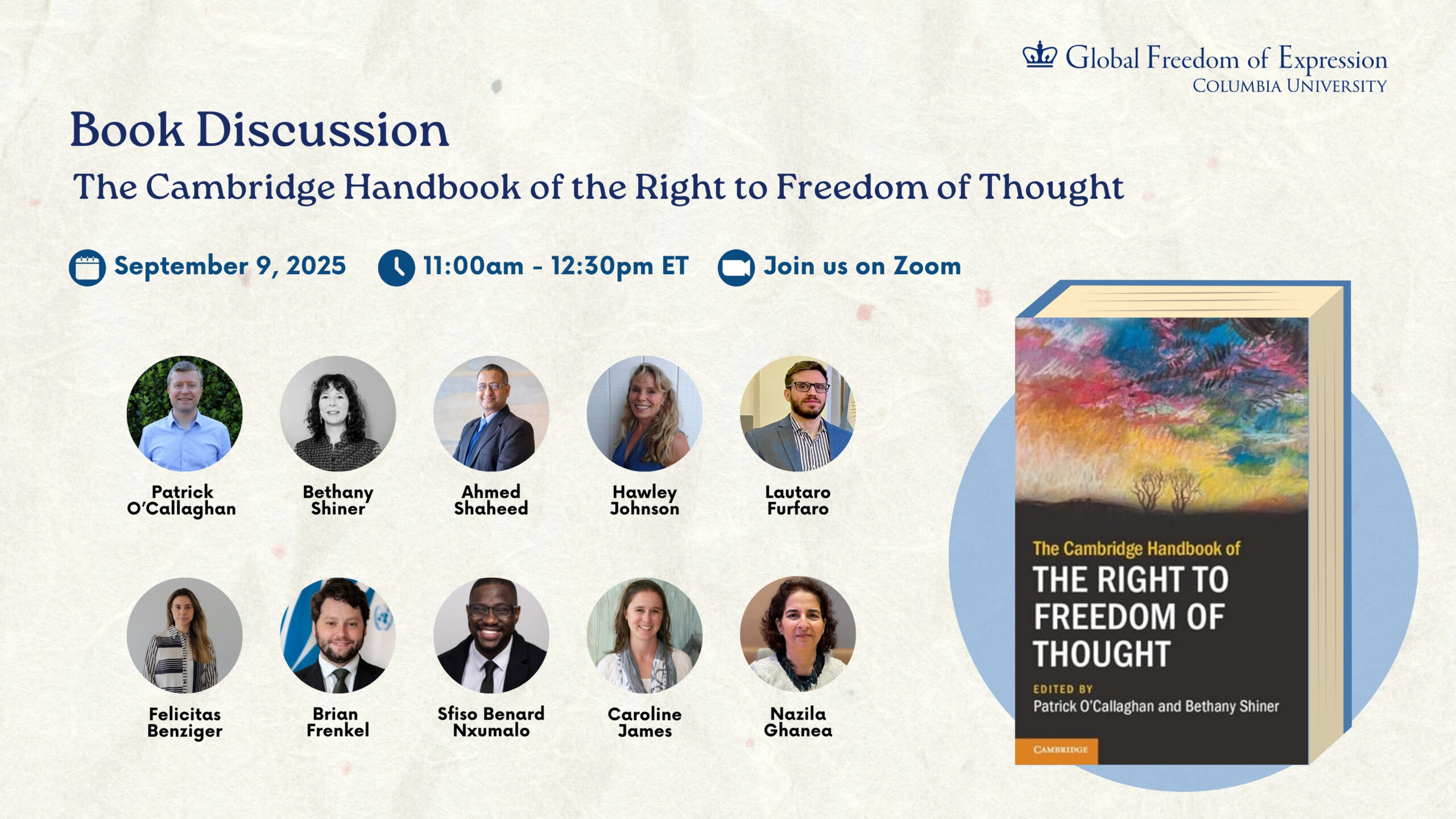

Patrick O’Callaghan, Professor of Law, University College Cork

Professor Patrick O’Callaghan teaches Jurisprudence and Tort Law at University College Cork (UCC). He is also Principal Investigator in the Law and the Inner Self Project (2022-2026), funded by a Research Ireland (Consolidator) Laureate Grant. Patrick joined UCC in 2014, having previously lectured at Newcastle University, UK (2007-2014). Before that, he was a researcher at the Centre for European Law and Politics (ZERP), Universität Bremen, Germany (2004-2007). Patrick’s background is in the legal protection of personality rights, as that field is conceptualised in the civilian private law tradition. This has led to an interest in theories of selfhood and questions about the role personality rights can play in safeguarding the opacity of the self. In this context, he has researched aspects of privacy law, the right to freedom of thought, the relationship between law and memory, including the right to be forgotten, the right to honour and reputation, and the historical development of personality rights. In contextualising his doctrinal research, Patrick draws on the methodologies of the field of law and humanities.

Bethany Shiner, Senior Lecturer in Law, Middlesex University

Bethany Shiner, Senior Lecturer in Law, Middlesex University

Bethany is Senior Lecturer in Law at Middlesex University, and has been teaching Public Law since 2015. She has taught English Legal System, Employment Law and Criminal Law. Bethany is completing her PhD at the University of Oxford on the right to freedom of thought under article 9(1) ECHR. Before joining academia, Bethany was a judicial review solicitor specialising in the Human Rights Act 1998. She was involved in the so-called ‘Iraq litigation’ which refers to hundreds of judicial review claims brought against the Secretary of Defence in regard to alleged human rights violations against Iraqi civilians and detainees during the Iraq war and occupation.

Ahmed Shaheed, Professor of International Human Rights Law, School of Law and Human Rights Centre, University of Essex; Former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief

Ahmed is Professor of International Human Rights Law in the School of Law and Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex. He directs the Human Rights Centre’s Religion and Equality Project, Project on Mobilising A Global Alliance to Counter islamophobia, and the Essex Summer School on Human Rights Research and Practice. He serves as an adviser on ‘hate speech’ to the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and is a member of the Panel of Experts on Freedom of Religion or Belief convened by the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe. He served as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief from 2016 to 2022 having previously served as the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran from 2011 to 2016. Hailing from the Maldives, Ahmed served as Foreign Minister of Maldives between 2005 and 2010, member of the Constitutional Assembly from 2004 to 2007, and led the government’s efforts to fast-track human rights and governance reforms between 2003 and 2007, which led to the transition to democracy in 2008. He is the founding chair of the Geneva-based think-tank, Universal Rights Group and is a Senior Fellow of the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights in Montreal. Ahmed’s areas of research are human rights implementation, UN’s human rights mechanisms, freedom of religion or belief, ‘hate speech’, human rights and emerging technologies, the freedom of thought, and progressive Islam. His reports to the UN have covered the freedom of thought, combatting antisemitism and islamophobia, upholding gender equality while promoting religious freedom, mainstreaming religious freedom in the sustainable development agenda, defending religious freedom while countering terrorism, and promoting freedom of expression. Ahmed has received numerous prestigious awards including the UN Foundation’s Global Leadership Award in 2015 for his work in promoting human rights nationally and internationally and a Presidential Medal from Albania in 2010 for his contributions to peace in the west Balkans.

Lautaro Furfaro, Senior Legal Researcher, Columbia Global Freedom of Expression; Professor of International Human Rights Law and Philosophical Foundations of Human Rights, University of Buenos Aires

Lautaro Furfaro is a legal researcher at Columbia Global Freedom of Expression. He is an international lawyer specializing in International Human Rights Law and International Law. He holds a Master of Laws in International Legal Studies from New York University Law School (2022), where he received the convocation award “Public Interest Law Prize” for demonstrating a clear commitment to public service and significant causes of public interest. He is a lawyer (J.D.) who graduated with honors from the University of Buenos Aires School of Law, specializing in International Law. Lautaro is currently an Adjunct Professor at the University of Buenos Aires School of Law, where he teaches International Human Rights Law. He is also co-Professor in the course Philosophical Foundations of Human Rights in the Master of International Human Rights Law at the University of Buenos Aires. Furthermore, he is an Assistant Professor of International Law in the foreign relations program at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella.

Hawley Johnson, Associate Director, Columbia Global Freedom of Expression

Hawley Johnson, Associate Director, Columbia Global Freedom of Expression

Dr. Hawley Johnson is the Associate Director of Columbia Global Freedom of Expression. Since 2014 she has managed the development of the Case Law Database which hosts analyses of seminal freedom of expression court rulings from more than 130 countries. Hawley has over twelve years of experience in international media development both academically and professionally, with a focus on Eastern Europe. From 2013-2014 she worked with the award-winning Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project to launch the Investigative Dashboard (ID), a joint effort with Google Ideas offering specialized databases and research tools for journalists in emerging democracies. Previously, as the Associate Director of the Media and Conflict Resolution Program at New York University, she oversaw the implementation of over eight US government sponsored media development programs in eleven countries. In 2012, she completed her Ph.D. in Communications at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Her dissertation – a study of the evolution of media development policies in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo and Macedonia – was grounded in extensive field research in the region. She has a M.A. from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a B.A. in International Affairs from the School of International Service at American University.

Felicitas Benziger, Post-doctoral researcher at University College Cork

Felicitas Benziger, Post-doctoral researcher at University College Cork

Felicitas is a post-doctoral researcher at University College Cork (UCC) where she works on the Law and Inner Self research project, which is funded by an Irish Research Council (Consolidator) Laureate Grant (IRCLA/2022/2628) and led by Dr. Patrick O’Callaghan. Felicitas first studied law in Germany and completed the German First State Exam and a degree in German law with specialisation in public international and EU law at Freie Universität Berlin. She furthermore holds a LLM in international law from University College London and completed her PhD (Thesis: Self-Determination of Peoples in the Context of Supranational Governance) at Middlesex University London.

Brian Frenkel, Professor of the European and African Human Rights Systems at the Master’s Degree in International Human Rights Law, University of Buenos Aires

Brian Frenkel, Professor of the European and African Human Rights Systems at the Master’s Degree in International Human Rights Law, University of Buenos Aires

Lawyer graduated with honors from the Faculty of Law of the University of Buenos Aires, he completed a Master’s Degree in International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights at L’Académie de droit international humanitaire et de droits humains à Genève, in Switzerland. He was Advisor on Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs at the Permanent Mission of Israel to the UN and other international organizations in Geneva. Previously, he served as advisor to the Ministry of Defense—National Directorate of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law—and to the Program for the Implementation of International Human Rights Treaties of the Office of the National Public Defender. He currently serves as an international consultant and legal researcher.

Sfiso Benard Nxumalo, Reading for a Doctor of Philosophy in Law, Faculty of Law, Oxford University

Sfiso Benard Nxumalo, Reading for a Doctor of Philosophy in Law, Faculty of Law, Oxford University

Sfiso Benard Nxumalo is reading for a Doctor of Philosophy (DPhil) in Law at the Faculty of Law at Oxford University. He holds a Bachelor of Civil Laws (BCL) from the University of Oxford and a Bachelor of Laws from the University of the Witwatersrand. His research for the DPhil concerns the philosophical purviews of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and African Legal Theory. He is an Ismail Mahomed Fellow, Chevening Scholar, FirstRand Foundation Scholar, Skye Foundation Fellow and Oppenheimer Memorial Trust Scholar. He is an admitted Advocate of the High Court of the Republic of South Africa. He teaches constitutional law and administrative law at Brasenose College as a stipendiary lecturer and contract law at Balliol College as a tutor. He is the President of the Oxford Law Black Alumni Network and a former Graduate Research Resident at the Bonavero Institute of Human Rights. He was also awarded the Samuel Pisar Travelling Fellowship in Human Rights to intern at the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Prior to beginning his studies at Oxford, Sfiso served as a law clerk to Justice Sisi Khampepe and Justice Steven Majiedt at the Constitutional Court of the Republic of South Africa. He also worked as a candidate attorney at Bowmans, a leading law firm in Africa.

Caroline James, Editor, Columbia Global Freedom of Expression; Advocacy Coordinator, amaBhugane Center for Investigative Journalism

Caroline James is a South African freedom of expression lawyer. Since 2022 she has been the advocacy coordinator for the amaBhugane Center for Investigative Journalism. She completed her M.A. at Queen’s University in Canada has BA(Hons) and LLB degrees from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her research interests are in constitutional and human rights law – particularly the way in which power is held to account. Caroline previously worked as the freedom of expression lawyer at the Southern Africa Litigation Centre in Johannesburg where she worked with lawyers and organizations in southern Africa litigating and advocating for the right to freedom of expression and association. Caroline has also worked as a judge’s clerk at the South Gauteng High Court in Johannesburg.

Nazila Ghanea, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief

Nazila Ghanea, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief

Ms. Nazila Ghanea assumed her mandate as Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief on 1 August 2022. Ms. Ghanea is Professor of International Human Rights Law and Director of the MSc in International Human Rights Law at the University of Oxford. Prior to that, she was Senior Lecturer at the University of London (2000-2006), and she has also previously taught in the People’s Republic of China (1993-1994). She has researched and published widely in international human rights law and served as consultant to numerous agencies. Though her nearly 30-year career has been rooted in academia, Ms. Ghanea’s academic work has often connected with multilateral practice in international human rights law. She has contributed actively to networks interested in freedom of religion or belief and its interrelationship with other human rights, and advised states and other stakeholders. In her professional activities, she has taken every opportunity to support the promotion and application of principled understandings of human rights, including freedom of religion or belief. She has supervised well over 100 master’s dissertations and doctorates and served on doctoral panels internationally. She has also co-authored a 700-page publication by Oxford University Press that addresses freedom of religion or belief and is focused on the UN record.

First Panel: “Introduction to the Handbook”

Q1. How should we distinguish the forum externum of the right to freedom of thought from freedom of expression? And if we do distinguish them, should courts apply the same standards when assessing interference, or do you think freedom of thought requires a stricter or different test than that used under freedom of expression?

Many civil and political rights have both a forum internum and a forum externum. So, for example, under the right to privacy, mental privacy is a different category to the privacy and confidentiality of one’s correspondence. What distinguishes the right to freedom of thought from other civil and political rights, including the right to freedom of expression, is that the forum internum takes on special significance. In fact, we might even argue that protection of the forum internum is the raison d’être of the right to freedom of thought. Understood in this way, it might be more accurate to speak in terms of a right to freedom of unmanifested thought which ought to have absolute protection. Once this unmanifested thought is manifested in our thought and/or behaviour, following Mill’s classic harm principle and the wording of international law, it no longer enjoys absolute protection in principle because it has the capacity to interfere with the rights of other people. If the manifestation of thought does warrant the protection of the law, it is subject to qualified protection only e.g. through the right to freedom of expression. We could say that this constitutes the forum externum of the right to freedom of thought although in actuality there has been no real legal guidance on what the forum externum of the right to freedom of thought is as far as it could be distinguished from expression or religious practice, for example. So, the question of how we should distinguish between the manifestation of expression and thought is unclear but might have something to do with the characteristic of the expression (or practice).

Q2. [Is there any judicial] decision or theory on the algorithm of thought?

Internationally, we found relatively few court decisions that deal squarely with the right to freedom of unmanifested thought. But we see scope for innovative pleadings in future cases, especially in the face of emerging socio-technical developments. These cases will have to deal with one of the central concerns of the book: at what point do thoughts warrant the attention of the law? Some of our behaviour (and thinking) may be quite straightforward, uncontroversial and even algorithmic in the sense of ‘first-order thinking’ as opposed to ‘second-order thinking’. Should this be protected by the law? Scholars in our book have put forward different and sometimes opposing proposals for tests as to when the right to freedom of thought is engaged. For example, Ligthart and van de Pol adopt the Campbell and Cosans v UK test of the European Court of Human Rights (is the thought sufficiently cogent, serious, cohesive and important to merit protection) whilst McCarthy-Jones and Walmsley challenge the idea that the right only protects the internal silent process of thinking (i.e. that the right ought to also protect ‘extended-thought’ and ‘thoughtspeech’).

Q3. Do you think that despite the UDHR, ICCPR, and the African, European, and American Charters, freedom of thought is sufficiently protected nowadays? Are these legislations enough, given the many violations of freedom of thought and expression?

The legal realists drew an important distinction between the law in the books and the law in action. Of course, it is one thing to say that the right to freedom of thought is adequately protected in international treaties, constitutions and high-level legislation. But it is quite another to say that this is so in practice. One of the most important themes of our book is exploring the distinction between the law in action and the law as written. Even in those jurisdictions where the right seems to have extensive protection in domestic law, we find evidence that more can be done to safeguard the right in practice. Some of this can be explained by the fact that the right is still underdeveloped and not well understood. One factor that may help fill the lacuna between law and practice is the emerging push to develop international, regional and domestic standards of human rights protection in the context of neurotechnology (see Istace and Van de Heyning). We hope that our books makes a positive contribution towards increasing the right’s profile in the context of neurotechnology and beyond.

Second Panel

Regional Perspectives on Freedom of Thought – Inter-American System

Q1. In the short-term [Inter-American] regional context, what do you see as the most realistic structural remedy for pilot cases where the right to thought might be violated?

What the appropriate structural remedy would be depends on the context and facts pertaining to the violation. An appropriate remedy for the harm incurred by state propaganda will differ from a remedy for the harm caused by a malfunctioning, unsecure or surveilling commercial neurotechnology device. For some violations of the right to freedom of thought it is difficult to imagine what form of restitution could apply given the nature of the harm for the individuals impacted. How can the mind be returned to what it was before the violation? For the individual, depending on the violation compensation and rehabilitation may be necessary. Immediate remedies may also include criminal prosecutions, administrative reforms or some form of sanction against corporation. Of course, legislation prohibiting the offending conduct, system or pattern is necessary, but we hope that such legislation would be put in place preemptively not ex post facto. This is why a specific focus on how to protect the right to freedom of thought within the Inter-American human rights system is necessary. Lautaro Furfaro’s suggestion during the book launch discussion that the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression acts as a driving force in setting standards on the right by creating a focused line of work on freedom of thought (alone or in relation to specific issues such as neurotechnologies) would be transformative.

Regional Perspectives on Freedom of Thought – European System

Q1. When reviewing the jurisprudence you focused on some cases involving parents and their “parental consciousness” (choosing a name, sexual education at schools, religion, etc). I understand the approach from the Commission and the Court, mainly avoiding to refer to them. Yet, how do you believe it is possible to address freedom of thought by children? It should be focused on the parent -as with the Protocol 1?- or the child -as an agent him/herself?

Using parents as the procedural vehicle for FoT claims in the context of freedom of education under Article 2 of Protocol No. 1 is justified and important from the perspective of parental conscience. At the same time, it risks sidelining children’s own rights under Article 9 ECHR, which applies to “everyone,” including minors. Article 14 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) reinforces this by recognising children’s FoT alongside parental guidance in line with evolving capacities. A dual approach seems preferable: parental conscience claims remain under Article 2 of Protocol No. 1, while children’s direct FoT rights should be recognised under Article 9 when they are personally affected as right holder (the challenge, of course, will be determining when and how a child could realistically claim this right). This model respects parents’ role while affirming children as independent rights-holders, bringing the ECHR closer in line with the CRC.

Q2. Looking at the current state of affairs, you refer to new technologies as a challenge to FoT. In the era of social media, do you think that states may have obligations to prevent and combat misinformation and disinformation since they can misguide people and affect their freedom of thought?

Being an absolute right limited to the forum internum, States must not interfere with our thoughts. The real challenge of misinformation and disinformation therefore lies in the conditions under which thought is formed. States clearly have a negative obligation not to engage in manipulation or practices that distort the free development of thought and personality, but whether they also carry a positive duty to combat disinformation is more delicate. Any attempt to regulate “truth” risks sliding into censorship and undermining both freedom of expression and FoT. A more balanced approach would read Article 9 alongside Article 10: the State’s role is not to dictate content, but to secure the condition (e.g. media pluralism, transparency, and education) that enable individuals to form their thoughts and personalities freely. Protecting FoT in the digital age is therefore less about suppressing particular ideas than about safeguarding the conditions in which everyone can exercise their mental autonomy.